Usually, when you think of China, you think of three things:

- Communism

- Martial arts

- Good food

If you’ve delved a little deeper into the “communism” subcategory, you’ve most definitely heard of the social credit system. How it works is simple: the CCP assigns each citizen a number. If you commit any sort of action the CCP deems unsatisfactory, they dock your social credit score. The CCP has cameras installed everywhere that will allegedly document each and every time you commit a faux pas. If Instagram is to be believed, jaywalking too many times can tank your score and ban you from trains. Forget your library books? Hope you didn’t want a loan.

This draconian system has become so infamous that U.S. government officials have voiced their disapproval, with former vice-president Mike Pence saying in 2018: “[B]y 2020, China’s rulers aim to implement an Orwellian system premised on controlling virtually every facet of human life.”

Because of the attention the social credit system has received online, it’s been the source of many memes. If there’s a post showcasing a Chinese city or tourist attractions within China, you can expect to find at least one comment saying something along the lines of: nice try CCP. +100000 social credit

If China was able to detect a person’s blood from just a blurry security camera frame, the U.S. would stand no chance. We’d just have to lay there and give up if World War 3 ever erupted. How do you even measure up against crazy technology that can track the genetic code of any of the 1.4 billion people in China?

Turns out, we don’t have to worry about that! No country on Earth has the sophisticated level of technology necessitated by that sort of social credit system. In fact, most Chinese people have no clue of what it is.

Background

China’s State Council issued a national roadmap to build a “social credit” framework in June 2014, with a target by 2020. This plan is written vaguely and speaks of no real, grounded action. In practice, the 2020 target has been more of a planning milestone than a hard deadline, and by late 2020, the government was still issuing new guidelines to refine the project. Even in the present, any plans for it are still flimsy and vague.

There are three kinds of credit that falls under the umbrella of the social credit system; credit for businesses, a blacklist for citizens and companies, and a moral credit. Credit for businesses is just an American credit score with Chinese characteristics, the blacklist is based on financials, and moral credit is a way to encourage civil behavior.

China’s blacklists are made for debtors who have the requisite ability to pay back debt, yet refuse to do so. Broad “social credit” (社会信用) or the moral part differs from the blacklist; if you have a bad credit record and wind up on a blacklist, not jaywalking or calling out the government online, you can expect punishments like being prohibited from buying expensive plane tickets or enrolling your kid in private school.

In 2020, the National Development and Reform Commission noted that the program was designed to “deter commercial fraud, tax and debt evasion” among firms and individuals. Chinese courts have been compiling lists of judgment defaulters – people who failed to honor their debts despite having the capital to do so – and using them to bar those individuals from high-speed trains and planes. Similarly, regulators publish lists of companies with bad credit (for example, those caught in food safety or environmental violations) that can restrict their ability to bid on government projects or receive loans.

Companies have their own ratings: firms are evaluated on whether they pay taxes on time, obey safety and product standards, and fulfill contracts. High-scoring companies (those with clean records) enjoy business perks such as easier access to loans and fewer bureaucratic hurdles. So, as you can gander, the “social credit system” is a loose mixing of the 3 subsections of business credit, blacklists, and trustworthiness. Your 89,112 social credit score will not tank to the negatives if you post a meme of Xi Jinping as Winnie-the-Pooh.

Even still, there is no nationalized social credit system. There is no number you get from the government that goes down when you fail to pay back a loan or anything else. What there are instead are blacklists.

But where does the trustworthiness aspect come in?

Case Study: Rongcheng, Shandong

Local governments have been the real laboratories for the moral-trustworthiness aspect of social credit. A few programs have sprung up in 40-some Chinese cities after the 2014 planning document was released.

In Rongcheng (Shandong province), a locally-designed credit program, gave each adult citizen 1,000 starting points and adjusted them for good or bad actions. Residents lost a few points for infractions like a traffic ticket and could earn points (sometimes 5–30 points) for community service, charitable donations, or winning a civic award. The city then translated total points into a grade (from A+++ down to D) and offered perks to the top scorers for instance, free bike rentals, winter heating discounts, or lower loan rates.

Rongcheng’s city hall even had billboards honoring “civilized families” and community heroes (parents caring for elders, traffic-cop heroes, etc.) as part of its local credit campaign.

Most people only encountered the system when trying to register for a loan, job, or other big life events. In fact, some locals, as noted by foreignpolicy.com, “don’t even know [the system] exists” until they need it. Those who do notice it tend not to dread it: one man in Rongcheng grumbled that checking his score was an “extra step” but found he was already top-rated. He noted, “I’m an A – just like 90% of Rongcheng’s population”.

Rongcheng’s local pilot program has been revamped, and is now strictly voluntary. It affects mostly local services and benefits, and does not feed into any national database or machine-learning score. Rongcheng and other cities are no longer able to punish citizens for anything that is not already illegal.

Case Study: Liaoning and Other Local Initiatives

Other provinces have tried their own versions. Liaoning, for example, floated adding blood donations into its credit framework. A provincial statement suggested rewarding residents who voluntarily gave blood as a way to “improve overall health outcomes”. However, this idea immediately sparked controversy and state media stepped in to say that voluntary acts like blood donation “have nothing to do with people’s creditworthiness”. China Daily noted that personal credit records traditionally cover financial and legal behaviors, not moral deeds. Officials suggested it would be better to encourage donors through medical benefits (like priority for blood transfusions) rather than by credit scores.

Liaoning’s case shows that not every local trial reflects central policy. Across China, dozens of cities and counties have piloted adult versions of getting a gold star in kindergarten, but these remain experimental. When cities levied punishments against their citizens in their test programs, the Mercator Institute for China Studies writes that the central government made clear that “scores could not be used to penalize citizens and that only formal legal documents could serve as grounds for penalties.“

What’s wenming, and why does it matter?

These systems are part of a broader campaign to promote orderly behavior in a nation that has undergone rapid urbanization and modernization. You can’t modernize a country of 1.4 billion people without also modernizing their behavior; at least, that’s the government’s thinking.

Just 50 years ago, China was one of the poorest countries on Earth. In 1978, its per capita GDP was twice lower than sub-Saharan Africa. Most of the population lived in the countryside, often with little access to education, healthcare, or roads, let alone traffic laws. Then came reform, urbanization, and a fast-track to becoming the world’s second-largest economy. The country evolved, but not social norms.

It’s pretty difficult to instill modern civic behavior across megacities that seem to spring up overnight, full of people who, just a generation ago, were living in villages. China’s leaders are turning to testing out these programs and things such as public shaming, which, in theory, deters bad behavior. In a collectivist society where “face” (how people view you) carries heavy weight, being called out publicly can be far more effective than a simple ticket.

Kernels of Truth

This is where the public shaming comes in. Rumors usually stem from kernels of truth, and in the case of the social credit system, it is no different. Some Chinese cities do have billboards that display blacklisted citizens on billboards. These people “are almost exclusively persons who have violated laws and regulations or not fulfilled court orders, rather than persons who have breached unspecified moral norms.“

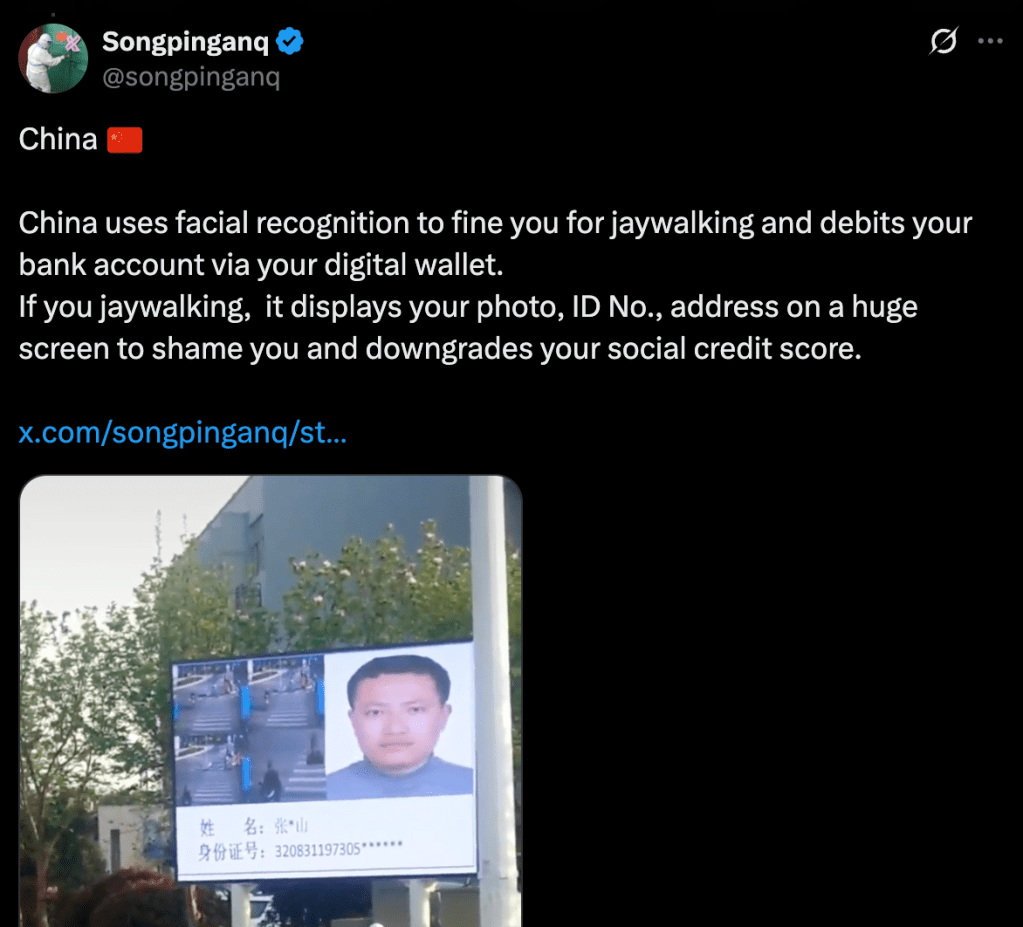

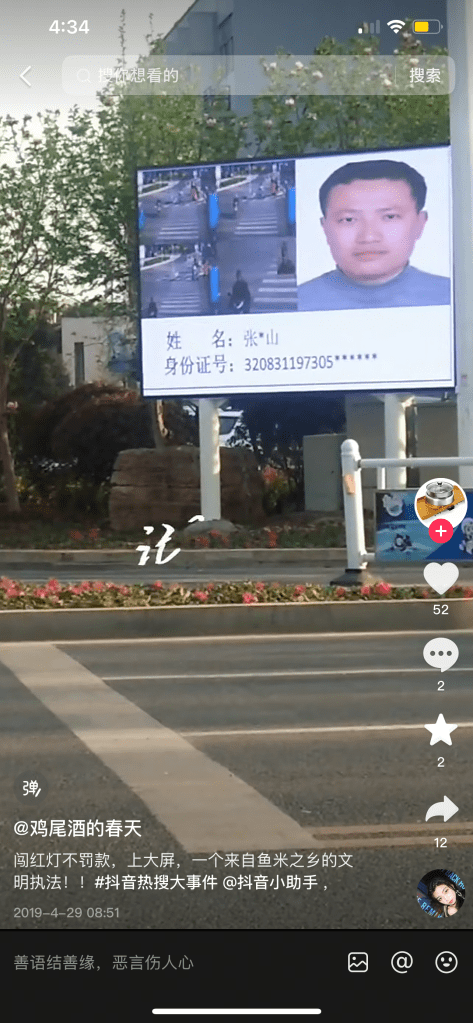

In that same vein, another often-repeated rumor is that cameras in China will photograph jaywalkers, remove money from their bank accounts, and then dock their social credit points.

The original video this tweet linked was posted on April 29, 2019 and showed faces of people who’d run red lights, not jaywalked, as shown in the photos on the billboard. It was posted with the caption, “闯红灯不罚款,上大屏,一个来自鱼米之乡的文明执法!!” that roughly translates to, “Running a red light doesn’t get you fined, it gets you on the big screen. A display of civilized law enforcement from the land of fish and rice! (a poetic way of referring to China).”

It is a somewhat common phenomenon to publicly shame jaywalkers in China. Travel YouTuber jakenbakelive posted a video of his own experience.

This is entirely separate from any social credit test drives, and is another government incentive to promote “wenming” (文明), or “civilization.”

Myths vs. Reality

Misconceptions have flourished in international coverage. Some common myths and the facts behind them:

- Myth: Every Chinese person has one social credit score. Reality: There is no single, countrywide score. Instead, China has many separate systems for different groups and purposes (the blacklists, business credit, the local opt-in reward systems). Legal experts emphasize that the so-called Social Credit System is actually “an ecosystem of initiatives” rather than one program. The Mercator Institute for China Studies notes: “such a score simply does not exist”. People may have multiple credit files (e.g. financial and legal records) but nothing like a centralized “trustworthiness meter.”

- Myth: China is constantly surveilling citizens’ every move and downgrading them in real time. Reality: The social credit system does not rely on live monitoring of speech or minor personal choices. This is a misconception that arises from misunderstandings of local government initiatives as well as punishments like public shaming. No country on Earth currently has the technological capacity to create and manage such a system, especially not China, with 1.4 billion citizens.

- Myth: Private credit programs (like Alipay’s Sesame Credit) are part of the government’s system. Reality: This is a widespread confusion. Alipay’s Sesame Credit (Zhima Credit) is a private credit score run by Alibaba. Alipay is the Chinese Venmo/Paypal/Zelle, except everyone uses it and no one bothers with cash or credit cards, save for the elderly and tourists. Sesame Credit operates as a consumer loyalty service where users opt in and receive rewards based on their use of Alibaba’s services. It is not an official arm of China’s social credit system. Observers note that media often “conflate” Sesame with the national program, but the two are distinct. Wired magazine explains: “As yet, there’s no one social credit system…[and] private versions are operated by companies such as Ant Financial’s Zhima Credit… They aren’t part of the official system”.

- Myth: Even trivial misbehavior will lead to draconian punishment like travel bans or job losses. Reality: By 2018, Chinese regulators reported banning people from buying 17.5 million plane tickets and 5.5 million train tickets nationwide. However, this falls into the blacklist part of the system. These punishments were solely for judgement defaulters, or people who have been found by a court to pay damages yet continue to not pay them despite having the funds. Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, answered this when an interviewer compared it to New York revoking your license if your accrued state debt is above $50,000: “It’s the same concept. and I think when there’s a court judgment in play, a lot of countries don’t have as much problem having these auxiliary or supplementary consequences […] The idea is that you’ve had your due process and now you should be doing it. Sometimes it doesn’t seem to make much sense. Suspending driver’s licenses in the US is going to make it harder for you to earn money to pay back those judgments. In China, the idea is that most of these awards are going to be monetary, and you shouldn’t be spending a lot of money if you haven’t paid back this award. Your money should be going to fix that problem.”

Official Perspective and Recent Developments

Chinese authorities describe social credit in terms of honesty in business and society. The system is frequently linked to phrases like “honesty, law, credit and cultivation” (信用、法治、文明) in official documents. In December 2020, the State Council’s guidelines highlighted learning from global experience and following international norms. They promised to “promote high-quality development” of the system, deter dishonest behavior, and ensure that data practices do not violate personal privacy. In practice, this means regulations on how financial firms and tech companies can collect and share user data. Beijing appears determined to keep the program within the bounds of existing law: the guidelines explicitly say any use of social credit data must be handled according to law.

At the same time, Chinese officials recognize the program is a work in progress. The government has repeatedly delayed full integration and remains light on clear details about a unified national plan. Even though earlier targets have shifted, leaders continue to reinforce the campaign as a way to reduce fraud and build trust in markets. As one Chinese sociologist put it, decades of weak trust in society (partly a legacy of political turmoil) created “anxiety” that the party now hopes to assuage through better data-sharing and enforcement.

In short, China’s social credit campaign is more mundane than many portrayals. It’s a blend of market-based credit reporting and incentives for good behavior, scaled up with digital tools.

So… we’re not in Black Mirror yet?

As of right now, no. That does not mean that something like a true social credit system couldn’t crop up in the future. As it stands, though, it seems highly unlikely, especially because the modern conception of the social credit system comes from hyperbole and lumping together the Chinese blacklists, sparse trustworthiness systems, and credit for businesses. For example, the systems used in some cities were combined with the public humiliation punishments for jaywalking as well as the punishments for being on a blacklist to generate this idea of an Orwellian, omniscient system.

The few active social credit systems cannot even punish people for low scores because… well, the government’s scared of people getting angry. Overall, there is no national standard in place, and what stands is more analogous to the American credit score than anything else, as well as a reward system in local cities. The only national standard that is in place is for businesses and corporations.

Leave a comment